Art of Happiness the Reflections of Madame Du Chãƒâ¢telet

| Émilie du Châtelet | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Maurice Quentin de La Tour | |

| Built-in | (1706-12-17)17 December 1706 Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 10 September 1749(1749-09-10) (aged 42) Lunéville, Kingdom of France |

| Known for | Translation of Newton's Principia into French, natural philosophy which combines Newtonian physics with Leibnizian metaphysics, and advocacy of Newtonian physics |

| Spouse(s) | Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet-Lomont (m. ) |

| Partner(s) | Voltaire (1733–1749) |

| Children |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Influences | Isaac Newton, Gottfried Leibniz, Willem 's Gravesande |

| Signature | |

| | |

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet (French pronunciation: [emili dy ʃɑtlɛ] ( ![]() heed ); 17 Dec 1706 – ten September 1749) was a French natural philosopher and mathematician from the early 1730s until her death due to complications during childbirth in 1749. Her most recognized accomplishment is her translation of and commentary on Isaac Newton's 1687 volume Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica containing bones laws of physics. The translation, published posthumously in 1756, is all the same considered the standard French translation. Her commentary includes a contribution to Newtonian mechanics—the postulate of an boosted conservation constabulary for total free energy, of which kinetic energy of move is one element. This led to her conceptualization of energy as such, and to derive its quantitative relationships to the mass and velocity of an object.

heed ); 17 Dec 1706 – ten September 1749) was a French natural philosopher and mathematician from the early 1730s until her death due to complications during childbirth in 1749. Her most recognized accomplishment is her translation of and commentary on Isaac Newton's 1687 volume Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica containing bones laws of physics. The translation, published posthumously in 1756, is all the same considered the standard French translation. Her commentary includes a contribution to Newtonian mechanics—the postulate of an boosted conservation constabulary for total free energy, of which kinetic energy of move is one element. This led to her conceptualization of energy as such, and to derive its quantitative relationships to the mass and velocity of an object.

Her philosophical magnum opus, Institutions de Physique (Paris, 1740, first edition; Foundations of Physics), circulated widely, generated heated debates, and was republished and translated into several other languages within two years of its original publication. She participated in the famous vis viva debate, concerning the best fashion to mensurate the force of a body and the best means of thinking about conservation principles. Posthumously, her ideas were heavily represented in the most famous text of the French Enlightenment, the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, first published shortly after du Châtelet's decease. Numerous biographies, books and plays take been written about her life and work in the two centuries since her death. In the early 21st century, her life and ideas take generated renewed involvement.

Émilie du Châtelet had, over many years, a relationship with the author and philosopher Voltaire.

Contribution to philosophy [edit]

In addition to producing famous translations of works past authors such as Bernard Mandeville and Isaac Newton, Du Châtelet wrote a number of significant philosophical essays, letters and books that were well known in her time.

Because of her well-known collaboration and romantic involvement with Voltaire, which spanned much of her adult life, for generations Du Châtelet has been known as mistress and collaborator to her much better known intellectual companion. Her accomplishments and achievements have frequently been subsumed under his and, equally a result, even today she is often mentioned only within the context of Voltaire's life and work during the period of the early French Enlightenment. The ideals of her works spread from the ideals of individual empowerment to issues of the social contract.

Recently, nonetheless, professional philosophers and historians accept transformed the reception of Du Châtelet. Historical evidence indicates that Du Châtelet's work had a very pregnant influence on the philosophical and scientific conversations of the 1730s and 1740s – in fact, she was famous and respected past the greatest thinkers of her fourth dimension.[i] Francesco Algarotti styled the dialogue of Il Newtonianismo per le matriarch based on conversations he observed between Du Châtelet and Voltaire in Cirey.[ii]

Du Châtelet corresponded with renowned mathematicians such as Johann II Bernoulli and Leonhard Euler, early developers of calculus. She was also tutored by Bernoulli's prodigy students, Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis and Alexis Claude Clairaut. Frederick the Slap-up of Prussia, who re-founded the Academy of Sciences in Berlin, was her great admirer, and corresponded with both Voltaire and Du Châtelet regularly. He introduced Du Châtelet to Leibniz's philosophy past sending her the works of Christian Wolff, and Du Châtelet sent him a re-create of her Institutions.

Her works were published and republished in Paris, London, and Amsterdam; they were translated into German and Italian; and, they were discussed in the most of import scholarly journals of the era, including the Memoires des Trévoux, the Journal des Sçavans, the Göttingische Zeitungen von gelehrten Sachen , and others. Maybe most intriguingly, many of her ideas were represented in various sections of the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D'Alembert, and some of the articles in the Encyclopédie are a direct re-create of her work (this is an agile area of current academic research - the latest enquiry tin exist found at Project Vox, a Duke University enquiry initiative).

Biography [edit]

Pregnant places in the life of Émilie du Châtelet

Early life [edit]

Émilie du Châtelet was born on 17 December 1706 in Paris, the only daughter amongst six children. Three brothers lived to adulthood: René-Alexandre (b. 1698), Charles-Auguste (b. 1701), and Elisabeth-Théodore (b. 1710). Her eldest brother, René-Alexandre, died in 1720, and the adjacent brother, Charles-Auguste, died in 1731. Yet, her younger blood brother, Elisabeth-Théodore, lived to a successful old age, becoming an abbot and eventually a bishop. Two other brothers died very immature.[3] Du Châtelet besides had a half-sister, Michelle, who was built-in of her father and Anne Bellinzani, an intelligent woman who was interested in astronomy and married to an important Parisian official.[iv]

Her father was Louis Nicolas le Tonnelier de Breteuil, a member of the lesser dignity. At the time of Du Châtelet's birth, her begetter held the position of the Principal Secretarial assistant and Introducer of Ambassadors to King Louis Fourteen. He held a weekly salon on Thursdays, to which well-respected writers and scientists were invited. Her female parent was Gabrielle Anne de Froullay, Baronne de Breteuil.[5]

Early pedagogy [edit]

Du Châtelet'due south instruction has been the subject of much speculation, but aught is known with certainty.[6]

Among their acquaintances was Fontenelle, the perpetual secretary of the French Académie des Sciences. Du Châtelet'southward begetter Louis-Nicolas, recognizing her early brilliance, arranged for Fontenelle to visit and talk about astronomy with her when she was 10 years old.[vii] Du Châtelet'southward mother, Gabrielle-Anne de Froulay, was brought up in a convent, at the time the predominant educational institution available to French girls and women.[vii] While some sources believe her mother did non approve of her intelligent daughter, or of her married man's encouragement of Émilie's intellectual curiosity,[7] there are besides other indications that her mother not only approved of Du Châtelet's early education, only actually encouraged her to vigorously question stated fact.[viii]

In either example, such encouragement would have been seen every bit unusual for parents of their time and status. When she was small, her begetter arranged training for her in physical activities such as fencing and riding, and as she grew older, he brought tutors to the firm for her.[7] Every bit a result, by the age of twelve she was fluent in Latin, Italian, Greek and German; she was later to publish translations into French of Greek and Latin plays and philosophy. She received education in mathematics, literature, and science.

Du Châtelet too liked to dance, was a passable performer on the harpsichord, sang opera, and was an amateur actress. As a teenager, short of coin for books, she used her mathematical skills to devise highly successful strategies for gambling.[7]

Union [edit]

On 12 June 1725, she married the Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet-Lomont.[9] [notation i] Her marriage conferred the title of Marquise du Chastellet.[note 2] Like many marriages among the nobility, theirs was arranged. Every bit a wedding ceremony gift, her husband was made governor of Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy by his begetter; the recently married couple moved there at the finish of September 1725. Du Châtelet was xviii at the time, her husband thirty-four.

Children [edit]

The Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet and Émilie du Châtelet had three children: Françoise-Gabrielle-Pauline (30 June 1726 – 1754, married in 1743 to Alfonso Carafa, Duca di Montenero), Louis Marie Florent (born 20 Nov 1727), and Victor-Esprit (born 11 April 1733).[x] Victor-Esprit died as an baby in late summertime 1734, likely the last Dominicus in August.[xi] On 4 September 1749 Émilie du Châtelet gave nativity to Stanislas-Adélaïde du Châtelet (girl of Jean François de Saint-Lambert). She died as an infant in Lunéville on 6 May 1751.[12]

Resumption of studies [edit]

Afterwards begetting iii children, Émilie, Marquise du Châtelet, considered her marital responsibilities fulfilled and reached an understanding with her married man to live split lives while still maintaining one household.[13] In 1733, aged 26, Du Châtelet resumed her mathematical studies. Initially, she was tutored in algebra and calculus by Moreau de Maupertuis, a member of the Academy of Sciences; although mathematics was non his forte, he had received a solid educational activity from Johann Bernoulli, who as well taught Leonhard Euler. However by 1735 Du Châtelet had turned for her mathematical grooming to Alexis Clairaut, a mathematical prodigy known all-time for Clairaut'due south equation and Clairaut's theorem. Du Châtelet resourcefully sought some of French republic'south best tutors and scholars to mentor her in mathematics. On one occasion at the Café Gradot, a place where men frequently gathered for intellectual discussion, she was politely ejected when she attempted to join one of her teachers. Undeterred, she returned and entered later having men's article of clothing made for herself.[14]

Human relationship with Voltaire [edit]

In the frontispiece to Voltaire'south book on Newton's philosophy, du Châtelet appears as Voltaire's muse, reflecting Newton'southward heavenly insights down to Voltaire.

Du Châtelet may take met Voltaire in her babyhood at one of her male parent'due south salons; Voltaire himself dates their coming together to 1729, when he returned from his exile in London. However, their friendship adult from May 1733 when she re-entered society after the nativity of her third kid.[vi]

Du Châtelet invited Voltaire to alive at her country house at Cirey in Haute-Marne, northeastern France, and he became her long-time companion. There she studied physics and mathematics and published scientific articles and translations. To judge from Voltaire's letters to friends and their commentaries on each other's work, they lived together with great common liking and respect. Every bit a literary rather than scientific person, Voltaire implicitly acknowledged her contributions to his 1738 Elements of the Philosophy of Newton, where the capacity on eyes bear witness strong similarities with her own Essai sur l'optique. She was able to contribute farther to the entrada by a laudatory review in the Periodical des savants.[xv]

Sharing a passion for science, Voltaire and Du Châtelet collaborated scientifically. They prepare a laboratory in Du Châtelet's home. In a healthy competition, they both entered the 1738 Paris Academy prize contest on the nature of burn down, since Du Châtelet disagreed with Voltaire'south essay. Although neither of them won, both essays received honourable mention and were published.[16] She thus became the beginning woman to have a scientific paper published by the Academy.[17]

[edit]

Du Châtelet'south relationship with Voltaire caused her to give up most of her social life to become more than involved with her study in mathematics with the teacher of Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis. He introduced the ideas of Isaac Newton to her. Letters written by Du Châtelet explain how she felt during the transition from Parisian socialite to rural scholar, from "1 life to the side by side."[eighteen]

Final pregnancy and expiry [edit]

In May 1748, Du Châtelet began an matter with the poet Jean François de Saint-Lambert and became pregnant. In a letter to a friend she confided her fears that she would not survive her pregnancy. On the night of 4 September 1749 she gave nativity to a daughter, Stanislas-Adélaïde. Du Châtelet died on x September 1749 [19] at Château de Lunéville,[20] from a pulmonary embolism. She was 42. Her daughter died 20 months later.[21]

Scientific inquiry and publications [edit]

Criticizing Locke and the argue on thinking matter [edit]

In her writing, Du Châtelet criticizes John Locke'southward philosophy. She emphasizes the necessity of the verification of noesis through feel: "Locke's idea of the possibility of thinking matter is […] abstruse."[22] Her critique on Locke originates in her Bernard de Mandeville commentary on The Legend of the Bees. She confronts us with her resolute statement in favor of universal principles which precondition homo knowledge and activeness, and maintains that this kind of law is innate. Du Châtelet claims the necessity of a universal presupposition, because if there is no such beginning, all our knowledge is relative. In that mode, Du Châtelet rejects John Locke'south aversion of innate ideas and prior principles. She also reverses Locke's negation of the principle of contradiction, which would found the basis of her methodic reflections in the Institutions. On the contrary, she affirms her arguments in favor of the necessity of prior and universal principles. "Two and two could then make as well iv as 6 if prior principles did not exist."[ clarification needed ]

Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis' and Julien Offray de La Mettrie's references to Du Châtelet'southward deliberations on motility, free will, thinking matter, numbers and the fashion to do metaphysics are a sign of the importance of her reflections. She rebuts the merits to finding truth by using mathematical laws, and argues against Maupertuis.[23]

Warmth and brightness [edit]

Dissertation Sur La Nature et La Propagation du feu, 1744

In 1737 du Châtelet published a paper entitled Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu,[24] based upon her inquiry into the science of fire. In it she speculated that at that place may be colours in other suns that are not constitute in the spectrum of sunlight on Earth.

Institutions de Physique [edit]

Her book Institutions de Physique [25] ("Lessons in Physics") was published in 1740; it was presented as a review of new ideas in science and philosophy to exist studied by her 13 year old son, but information technology incorporated and sought to reconcile complex ideas from the leading thinkers of the fourth dimension. The book and subsequent contend contributed to her becoming a member of the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna in 1746.

Forces Vives [edit]

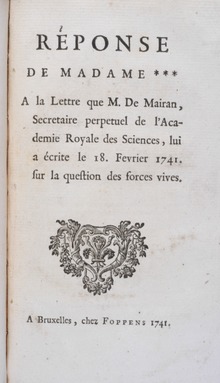

Réponse de Madame la Marquise du Chastelet, 1741

In 1741 du Châtelet published a book titled Réponse de Madame la Marquise du Chastelet, a la lettre que M. de Mairan. Dortous de Mairan, secretary of the Academy of Sciences, had published a set of arguments addressed to her regarding the appropriate mathematical expression for forces vives. Du Châtelet presented a spirited bespeak past point rebuttal of de Mairan'due south arguments, causing him to withdraw from the controversy.[26]

Immanuel Kant's start publication in 1747 'Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces' (Gedanken zur wahren Schätzung der lebendigen Kräfte) focuses on Du Châtelet'due south pamphlet against the secretary of the French Academy of Sciences, Mairan. Kant'southward opponent, Johann Augustus Eberhard accused Kant of taking ideas from Du Châtelet.[27]

Advancement of kinetic energy [edit]

Although in the early 18th century the concepts of force and momentum had been long understood, the idea of energy every bit transferable between unlike systems was yet in its infancy, and would non be fully resolved until the 19th century. It is now accustomed that the total mechanical momentum of a organization is conserved and none is lost to friction. Simply put, there is no 'momentum friction' and momentum can not transfer between different forms, and particularly there is no potential momentum. Emmy Noether later proved this to be true for all problems where the initial state is symmetric in generalized coordinates. Mechanical free energy, kinetic and potential, may be lost to another form, just the total is conserved in time. The Du Châtelet contribution was the hypothesis of the conservation of total free energy, as distinct from momentum. In doing so, she became the first person in history to elucidate the concept of free energy as such, and to quantify its relationship to mass and velocity based on her own empirical studies. Inspired by the theories of Gottfried Leibniz, she repeated and publicized an experiment originally devised by Willem 's Gravesande in which balls were dropped from unlike heights into a sail of soft clay. Each ball'due south kinetic free energy - as indicated past the quantity of material displaced - was shown to be proportional to the square of the velocity. The deformation of the clay was found to be straight proportional to the superlative the balls were dropped from, equal to the initial potential free energy. With the exception of Leibniz, before workers like Newton believed that "free energy" was indistinct from momentum and therefore proportional to velocity. According to this understanding, the deformation of the clay should have been proportional to the square root of the summit from which the balls were dropped. In classical physics the correct formula is , where is the kinetic free energy of an object, its mass and its speed. Energy must always have the aforementioned dimensions in any form, which is necessary to be able to relate it in different forms (kinetic, potential, heat . . .). Newton's work causeless the exact conservation of only mechanical momentum. A broad range of mechanical bug are soluble only if energy conservation is included. The collision and scattering of two point masses is one of them. Leonhard Euler and Joseph-Louis Lagrange established a more formal framework for mechanics using the results of du Châtelet.[28] [29]

Translation and commentary on Newton'south Principia [edit]

In 1749, the twelvemonth of Du Châtelet's death, she completed the work regarded equally her outstanding accomplishment: her translation into French, with her commentary, of Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (often referred to as simply the Principia), including her derivation of the notion of conservation of energy from its principles of mechanics. Published x years after her death, today Du Châtelet'due south translation of the Principia is still the standard translation of the work into French. Her translation and commentary of the Principia contributed to the completion of the scientific revolution in French republic and to its acceptance in Europe.[30]

Other contributions [edit]

Development of financial derivatives [edit]

She lost the considerable sum for the time of 84,000 francs—some of it borrowed—in one evening at the table at the Court of Fontainebleau, to carte cheats.[7] [31] To raise the money to pay dorsum her debts she devised an ingenious financing arrangement like to modern derivatives, whereby she paid tax collectors a fairly low sum for the right to their future earnings (they were allowed to keep a portion of the taxes they collected for the King), and promised to pay the courtroom gamblers part of these future earnings.[7]

Biblical scholarship [edit]

Du Châtelet wrote a critical assay of the entire Bible. A synthesis of her remarks on the book of Genesis was published in English language in 1967 by Ira O. Wade of Princeton in his book Voltaire and Madame du Châtelet: An Essay on Intellectual Activity at Cirey and a book of her complete notes was published in 2011, in the original French, edited and annotated by Bertram Eugene Schwarzbach.

Discourse on happiness [edit]

Du Châtelet wrote a monograph, Discours sur le bonheur, on the nature of happiness both in general and specialised to women.

Translation of the Fable of the Bees, and other works [edit]

Du Châtelet translated The Fable of the Bees in a free adaptation. She also wrote works on eyes, rational linguistics, and the nature of free will.

Back up of women'south education [edit]

In her first contained work, the preface to her translation of the Fable of the Bees, du Châtelet argues strongly for women'south education, particularly a strong secondary education equally was available for immature men in the French collèges. By denying women a good didactics, she argues, gild prevents women from condign eminent in the arts and sciences.[32]

Legacy [edit]

Du Châtelet made a crucial scientific contribution in making Newton's historic work more accessible in a timely, accurate and insightful French translation, augmented by her own original concept of energy conservation.

A main-belt pocket-sized planet and a crater on Venus have been named in her honor, and she is the subject field of three plays: Legacy of Light by Karen Zacarías; Émilie: La Marquise Du Châtelet Defends Her Life This evening by Lauren Gunderson and Urania: the Life of Émilie du Châtelet by Jyl Bonaguro.[33] The opera Émilie of Kaija Saariaho is about the last moments of her life.[34]

Du Châtelet is often represented in portraits with mathematical iconography, such as belongings a pair of dividers or a page of geometrical calculations. In the early on nineteenth century, a French pamphlet of historic women (Femmes célèbres) introduced a mayhap apocryphal story of Du Châtelet's babyhood.[35] Co-ordinate to this story, a servant fashioned a doll for her by dressing upwards wooden dividers as a doll; however, du Châtelet undressed the dividers and intuiting their purpose, made a circle with them.

Since 2016, the French Society of Physics (la Société Française de Physique) has awarded the Emilie Du Châtelet Prize to a physicist or team of researchers for excellence in Physics.

Duke Academy also presents an almanac Du Châtelet Prize in Philosophy of Physics "for previously unpublished work in philosophy of physics by a graduate pupil or junior scholar."[36]

On December 17, 2021, Google Putter honored Emilie Du Châtelet.[37]

Portrayal [edit]

Émilie du Châtelet is portrayed by the actress Hélène de Fougerolles in the docudrama Einstein'southward Large Idea.[38]

Works [edit]

- Scientific

- Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu (1st edition, 1739; 2nd edition, 1744)

- Institutions de physique (1st edition, 1740; 2nd edition, 1742)

- Principes mathématiques de la philosophie naturelle par feue Madame la Marquise du Châtelet (1st edition, 1756; second edition, 1759)

- Other

- Examen de la Genèse

- Examen des Livres du Nouveau Testament

- Discours sur le bonheur

See also [edit]

- Timeline of women in science

Explanatory notes [edit]

- ^ The Lomont suffix indicates the co-operative of the du Chastellet family; some other such branch was the du Chastellet-Clemont.

- ^ The spelling Châtelet (replacing the s by a circumflex over the a) was introduced by Voltaire, and has now go standard. (Andrew, Edward (2006). "Voltaire and his female protectors". Patrons of enlightenment. University of Toronto Press. p. 101. ISBN978-0-8020-9064-5. )

Citations [edit]

- ^ Grosholz, Emily (2013). Arianrhod, Robyn (ed.). "Review of Candles in the Dark: Émilie du Châtelet and Mary Somerville". The Hudson Review. 65 (iv): 669–676. ISSN 0018-702X. JSTOR 43489293 – via JSTOR.

- ^ La vie privée du roi de Prusse von Voltaire, p. 3

- ^ Zinsser, pp. xix, 21, 22.

- ^ Zinsser, pp. xvi–17; for a quite different business relationship, see Bodanis, pp. 131–134.

- ^ Detlefsen, Karen (ane January 2014). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Émilie du Châtelet (Summertime 2014 ed.).

- ^ a b Zinsser.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g Bodanis.

- ^ Zinsser (2006: 26–29)

- ^ Hamel (1910: five).

- ^ Zinsser, pp. 39 and 58.

- ^ Zinsser, pp. xl and 93.

- ^ D. West. Smith, "Nouveaux regards sur la brève rencontre entre Mme Du Châtelet et Saint-Lambert." In The Enterprise of Enlightenment. A Tribute to David Williams from his friends. Ed. Terry Pratt and David McCallam. Oxford, Berne, etc.: Peter Lang, 2004, p. 329-343. See besides Anne Soprani, ed., Mme Du Châtelet, Lettres d'amour au marquis de Saint-Lambert, Paris, 1997.

- ^ "Émilie, Marquise du Châtelet-Laumont (1706-1749) from OSU Dept. of Philosophy (archived)". Archived from the original on 17 Jan 2005.

- ^ Tsjeng, Zing (2018). Forgotten Women. pp. 156–159. ISBN978-ane-78840-042-8.

- ^ Shank, J. B. (2009). "Voltaire". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Detlefsen, Karen. "Émilie du Châtelet". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2014-06-07 .

- ^ Arianrhod (2012), p. 96.

- ^ "Emilie Du Châtelet -". www.projectcontinua.org . Retrieved 2016-03-31 .

- ^ Einstein's big idea, Johnstone, Gary, 1959-, McArdle, Aidan., Henderson, Shirley, 1965-, Lithgow, John, 1945-, Bodanis, David., Darlow Smithson Productions., WGBH Boston Video, 2005, ISBN1593753179, OCLC 61843630

{{commendation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ La vie privée du roi de Prusse by Voltaire, p. 58

- ^ Zinsser (2006: 278)

- ^ quoted in Ruth Hagengruber, "Emilie du Châtelet Between Leibniz and Newton: The Transformation of Metaphysics", in Emilie du Châtelet between Leibniz and Newton (ed. Ruth Hagengruber), Springer. p. 12

- ^ Hagengruber (2011: eight–12,24,53,54)

- ^ Van Tiggelen, Brigitte (2019). "Emilie Du Chatelet and the Nature of Fire: Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu". In Lykknes, Annette; Van Tiggelen, Brigitte (eds.). Women in Their Element: Selected Women'south Contributions To The Periodic System. Singapore: World Scientific.

- ^ Du Châtelet, Gabrielle Emilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil (1740). Institutions de physique. Paris: chez Prault fils. doi:10.3931/due east-rara-3844.

- ^ Smeltzer, Ronald Thou. (2013). Extraordinary Women in Science & Medicine: Four Centuries of Achievement. The Grolier Club.

- ^ Ruth Hagengruber: "Émilie du Châtelet between Leibniz and Newton: The Transformation of Metaphysics", in: Hagengruber, Ruth 2011: Émilie du Châtelet between Leibniz and Newton, Springer 1-59, p. i and 23, footnote iv and 113.

- ^ Hagengruber (2011)

- ^ Arianrhod (2012)

- ^ Larson, Hostetler, Edwards (2008). Essential Calculus Early Transcendental Functions. U.S.A: Richard Stratton. p. 344. ISBN978-0-618-87918-two.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hamel (1910: 286)

- ^ Zinsser, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Urania, Historical Play past Local Artist, Debuts with Complimentary Gallery Shows Archived 2016-03-twenty at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Libretto of Émilie Archived 2013-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zinsser, p. 13.

- ^ "Du Châtelet Prize | Section of Philosophy". philosophy.duke.edu . Retrieved 2020-09-01 .

- ^ Musil, Steven. "Google Putter honors French mathematician Émilie du Châtelet". CNET . Retrieved 2021-12-17 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ , Johnstone, Gary, 1959-; McArdle, Aidan; Henderson, Shirley, 1965-; Lithgow, John, 1945-; Bodanis, David, "Einstein's Large Idea", Darlow Smithson Productions, WGBH Boston Video, 2005, ISBN1593753179, OCLC 61843630

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

General sources [edit]

- "Projection Phonation". Duke University.

- Arianrhod, Robyn (2012). Seduced past logic : Émilie du Châtelet, Mary Somerville, and the Newtonian revolution (US ed.). New York: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-xix-993161-3.

- Bodanis, David (2006). Passionate Minds: The Great Beloved Affair of the Enlightenment. New York: Crown. ISBN0-307-23720-half-dozen.

- Ehman, Esther (1986). Madame du Chatelet . Berg: Leamington Spa. ISBN0-907582-85-0.

- Hamel, Frank (1910). An Eighteenth Century Marquise: A Report of Émilie Du Châtelet and Her Times. London: Stanley Paul and Company. OCLC 37220247.

- Hagengruber, Ruth, ed. (2011). Émilie du Châtelet between Leibniz and Newton . Springer. ISBN978-94-007-2074-9.

- Mitford, Nancy (1999). Voltaire in Beloved. New York: Carroll and Graff. ISBN0-7867-0641-4.

- Zinsser, Judith (2006). Dame d'Esprit: A Biography of the Marquise Du Châtelet. New York: Viking. ISBN0-670-03800-viii.

online review

- Zinsser, Judith; Hayes, Julie, eds. (2006). Emilie du Châtelet: Rewriting Enlightenment Philosophy and Science. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation. ISBN0-7294-0872-8.

External links [edit]

- Émilie Du Châtelet (1706-1749), Projection Vox

- Zinsser, Judith. 2007. Mentors, the marquise Du Châtelet and historical retentiveness.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Gabrielle Emilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil Marquise du Châtelet", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- "Émilie du Châtelet", Biographies of Women Mathematicians, Agnes Scott College

- The Portraits of Émilie du Châtelet at MathPages

- Voltaire and Émilie from the website of the Château de Cirey, accessed eleven Dec 2006.

- Correspondence between Frederick the Smashing and the Marquise du Châtelet Digital edition of Trier University Library (French and German text)

- St Petersburg Manuscripts, first digital and disquisitional edition by the Center for the History of Women Philosophers and Scientists in cooperation with the National Library of Russian federation

- Project Continua: Biography of Émilie Du Châtelet

- Lamothe, Lori. "Dangerous Liaisons: Emilie du Chatelet and Voltaire's Passionate Dearest Affair" at History of Yesterday

- Works by Émilie du Châtelet at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

News media [edit]

- Fara, Patricia (10 June 2006). "Love in the Library". The Guardian.

- "The scientist that history forgot," The Guardian xv May 2006.

- Object Lesson / Objet de Lux Commodity on Émilie du Châtelet from Cabinet (magazine)

- PhysicsWeb article: Émilie du Châtelet: the genius without a beard

- National Public Radio Morning Edition, 27 November 2006: Passionate Minds

- Women Scientists Today Link to CBC radio interview with author David Bodanis.

- Link to ARTE-Doku-Drama E = mc² – Einsteins große Idee. ARTE Tv set 26 April 2008, 12 March 2011.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89milie_du_Ch%C3%A2telet

0 Response to "Art of Happiness the Reflections of Madame Du Chãƒâ¢telet"

Post a Comment